Balance exercise programs are an effective way to prevent falls in older people. Exercises are mostly focused on controlling the center of mass while reducing the base of support, for example by standing on one leg. Balance control however, also requires adaptive responses that would require a person to either increase, or even reduce their base of support, by means of taking a step. Taking such a protective step is often the last resort to keep upright (and not fall) at the critical moment of slipping or tripping. Therefore, it seems logical that training people how to take correct, rapid and well-directed steps may be very valuable in the prevention of falls in older adults. Stepping ability typically has two components: volitional or proactive stepping (changing your walking pattern to proactively avoid a fall, such as taking a bigger step to step over an obstacle); and reactive stepping, which is the ability to respond to sudden changes in balance (for example, when slipping on a wet floor or tripping over an uneven surface).

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of trials using step training to reduce falls or fall risk factors. We included both volitional (e.g., stepping onto step targets in various directions) and reactive (e.g., exposure to slip or trip perturbations) step training.

WHAT DID WE FIND?

Astoundingly, step training can prevent falls in older adults by 50%. This reduction in falls is consistent across the type of step training (reactive/volitional), living circumstance (community/institutional) and the falls-risk of participants (healthy/high-risk).

An additional meta-analysis of revealed that these stepping interventions also improved known fall risk factors such as simple and choice stepping reaction time, single leg stance, timed up and go performance, but not muscle strength.

SIGNIFICANCE AND IMPLICATIONS

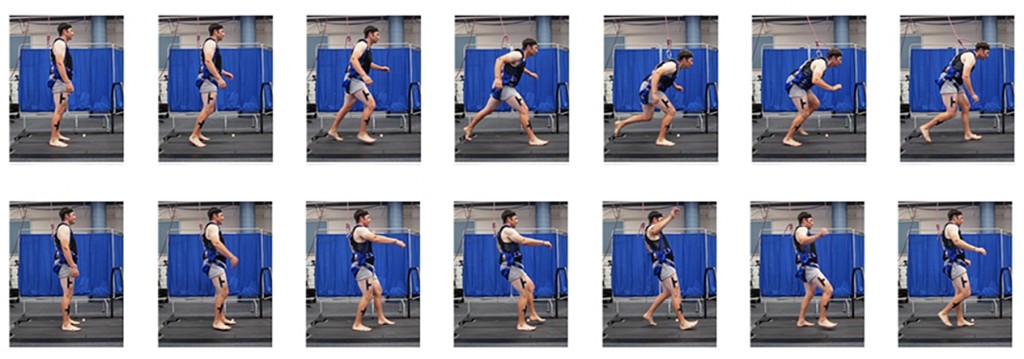

Our analysis shows that step training can significantly prevent falls by 50% in older people. Step training should be included in exercise programs designed to prevent falls. Step training can be done by asking people to take steps in various directions (volitional) or by exposing them to slips or trips in a protected environment (reactive). Both strategies work, but it is important that the training is performed in an upright position and undertaken in response to environmental challenges which mimic real-world fall situations. Some examples are stepping onto a target, avoiding an obstacle or responding to a perturbation.

Reactive step training requires a perturbation module and full-body harness to make it safe. While very effective, this training option is unfortunately not readily available in clinical practice. However, volitional step training can be done in various settings including group exercise classes or even in the person’s home. Future studies should aim to improve feasibility of reactive step training.

PUBLICATION

Okubo Y, Schoene D and Lord SR (2016). Step training improves reaction time, gait and balance and reduces falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Sports Medicine: Jan 8., doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095452.

I think this is quite possibly the most understated research finding in the area of falls prevention. I’ve cited your meta-analysis several times in presentations this year and now my colleagues have really come round to the the idea of integrating more psychomotor speed and reactive stepping training into rehab programs.

In the rehab setting safety is paramount, and so we are inclined to under-challenge our clients in case of an adverse event. Consequently, reactive stepping is just one of those activities that is not included enough in our programs. But a systematic review and meta-analysis of this quality cannot be ignored and we need to innovate with methods to train reactive stepping with little to no equipment.

I’d argue that although training reactions to external perturbations with a harness is best practice, there are other therapeutic activities that can be set up safely to train reactive stepping (with standby assistance of a therapist when needed). The tricky part is generating a perturbation in an unanticipated direction. Is there an reason why the perturbation must be external to the individual? I often exploit the variability in the intrinsic perturbations elicited with fast stepping on and off a BOSU (set up in a corner of a kitchen bench or beside a vertical pole, plus or minus therapist standing by). I’d love to see some research performed on the use of a simple BOSU for reactive stepping training. I’ve found a supplier of smaller bosus which are lower in height and less daunting for clients. If your team is interested in obtaining one to test their suitability for this purpose, please don’t hesitate to contact me and I’ll point you in the right direction.

About 18 months ago I presented at QLD Rehab Physiotherapists Network annual conference and played a video of a client doing an exergaming activity to train reactive stepping. It is one that I developed by recording prompts on an iphone and syncing it with a bluetooth headset. Since that time a few rehab units in Brisbane hospitals have adopted this exercise and set it up as a station in their balance classes. Our uni clinics are prescribing this exercise too. The feedback from the clients and clinicians was so positive that I decided to progress it and develop an app to facilitate independent practice of this particular exercise I’ll make it available in app stores in a few months at no cost or very low cost, so I’ll be sure to let you know when it’s downloadable. It will be called Clock Yourself.

Thanks for your contribution to the evidence base, I found it particularly inspiring and validating.

Meggen Lowry

Director & Principal Physiotherapist

Next Step Physio

You may be interested in the following study. Older adult Alexander technique practitioners walk differently than healthy age-matched controls. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2016.04.009

The Alexander Technique (AT) seeks to eliminate harmful patterns of tension that interfere with the control of posture and movement and in doing so, it may serve as a viable intervention method for increasing gait efficacy in older adults….The findings suggest that the older AT practitioners walked with gait patterns more similar to those found in the literature for younger adults. These promising results highlight the need for further research to assess the AT’s potential role as an intervention method for ameliorating the deleterious changes in gait that occur with aging.

cheers